In order to reach its long-term goal of becoming a universal currency, bitcoin needs to acquire two qualities that are essential to every form of sound money: privacy and fungibility. In the case of privacy, it’s important that the identities of the BTC transaction sender and receiver remain unknown to every unwanted third party. For fungibility, every bitcoin amount needs to have the same degree of acceptance for payments, regardless of the money’s origins. In other words, we need to make this global digital currency work just like physical cash.

This article will explain the current asymmetry between privacy and fungibility, while also introducing the ways in which the new Wasabi 2.0 wallet can bridge the two worlds. The problem: privacy vs fungibility.

Given the open ledger architecture of the Bitcoin network, watching all transactions is one of the features which guarantees the integrity of the financial policy. Seeing the amount getting sent in every transaction reassures every node that nobody breaks the rules by introducing unwanted inflation into the monetary system. And in some cases, revealing the identity behind an address creates an extra level of trust – as is the case of big exchanges, investment funds, charity foundations and fundraisers. Yet the issue is that every time the identity of an active address is revealed, everyone else’s privacy gets damaged. This is why obfuscation mechanisms are required.

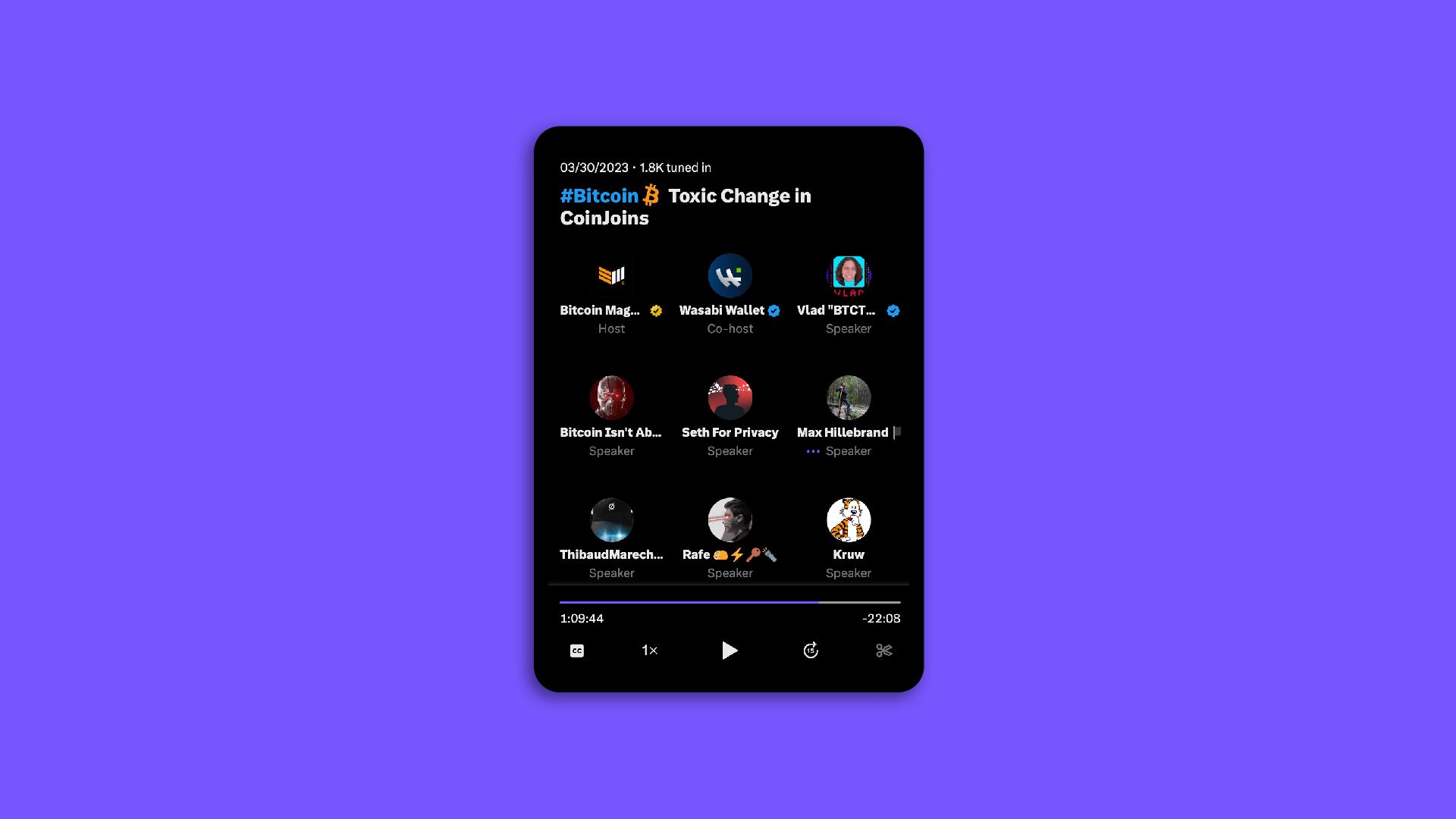

CoinJoins are a great way to increase the privacy of bitcoin senders, as they break the link between the current owner and the previous transactions. However, this obfuscation technique is observable on the public blockchain, almost always finds itself in a numeric minority as compared to other transactions and can therefore create fungibility issues.

In a perfect world, privacy should improve fungibility. But if there are only a few privacy users, then they can get rejected by other participants. In order for privacy to create fungibility, a certain tipping point needs to be reached: bitcoiners must mix their coins in an overwhelming majority and thus successfully obliterate any claim that using privacy hides criminal actions. Similarly, Bitcoin at large has managed to break away from its Silk Road reputation by onboarding more users with no criminal record, who transact in good faith in a completely legal way.

Another side of the debate concerns the fact that fungibility is a pretty utopian concept for technical, practical and economic reasons. Technically, not all bitcoins are created equal: they carry different cryptographic hashes, get added to the supply by different competing miners and change hands in different patterns that may please some users while displeasing others. Practically every Bitcoin node has its own blacklist and every miner can choose to not include transactions that come from unwanted addresses. Bitcoin enables censorship by design and it’s only through incentives and social norms that fungibility can work.

But then again, cash also gets tainted by every user’s fingerprints and may get censored according to serial numbers. Yet it’s thanks to everyone’s agreement that a one – dollar bill is equal with every other one – dollar bill regardless of its origins that we have economic fungibility and privacy is one of the socially-accepted benefits.

Last but not least, there’s the economic dimension of BTC fungibility. There are two extremes involved in this debate: the users of non-custodial wallets and the regulated custodians (exchanges, banks, and mutual funds). If all the coins get withdrawn from custodians, then there won’t be any government-controlled entities to undergo financial censorship – and therefore bitcoin becomes fungible within the technical and practical limits described above. On the other hand, the coins can also become fungible is the custodians get their hands on every unit – ironically, centralized KYC exchanges like Kraken and Coinbase are actually pretty good mixers which also grant the funds a fairly certain degree of fungibility. But fungibility must not come at the expense of turning bitcoin into an Orwellian money system, in which custodians have absolute control.

The bad news is that the amount of bitcoins deposited on exchanges has been constantly high for the last 5 years. These exchanges have become increasingly draconian in terms of rejecting specific transactions, and established policies against transaction privacy even in the absence of clear regulatory frameworks. The good news is that there is balance between the custodially-owned and the sovereign bitcoins and the amount of coins on exchanges doesn’t seem to increase too greatly. But since none of the ownership extremes is winning and we want a situation in which privacy generates fungibility, we need to start building bridges. In this design, we must consider the properties of cash and build both the tools and the social norms which help us always agree that every bitcoin unit is equal to any other one. Wasabi 2.0 marks a promising beginning in this direction.

Bridging Bitcoins with Wasabi 2.0

Launched in 2018 on the 10th anniversary of the Bitcoin White Paper, Wasabi 1.0 has proven to every privacy enthusiast that BTC is the only currency that they should be using. The combined power of the non custodial experience, the automatic routing of the internet connection via Tor, the sovereign setup which puts users in control of their public key without having to trust a third party and the easy CoinJoins still makes blockchain analysts scratch their heads in an attempt to make guesses. Furthermore, users can also access their hardware wallets in Wasabi – thus granting them a greater amount of privacy than most of the native applications. Nonetheless, the design of Wasabi 1.0 isn’t perfect. Users can still make privacy-damaging mistakes such as reusing addresses or combining private UTXOs with tracked ones for disastrous outcomes that reveal a lot of information. Another big mistake is also that of recombining UTXOs after a CoinJoin – it basically defeats the purpose as the previous state of the coins gets reconstructed and a careful analyst will simply bypass the CoinJoin part to keep on following the money. Then there are the deterring reasons which have kept users away from Wasabi. The biggest one being the minimum amount to CoinJoin: back in late 2018, 0.1 BTC was approximately $400; but at the new all-time high of $69k, one tenth of a bitcoin was equivalent to $6900.

Many users didn’t CoinJoin with Wasabi specifically because they could not afford to but thanks to the WabiSabi protocol that’s embedded in version 2.0, smaller amounts are welcome to get mixed with the bigger ones coming from whales. Also, there’s the privacy FUD which made bitcoiners fear the idea of mixing. It’s exactly the “your BTC might get dirtier” argument that influencers such as Trace Mayer have been pushing for years. The idea behind CoinJoins is to make every monetary unit just as clean and just as dirty – and therefore fungible. Wasabi 2.0 definitely makes it easier for every user to CoinJoin, thanks to the auto-pilot experience which automatically makes the best decisions for your privacy. The software is open source and you’re strongly encouraged to verify it, so every ounce of trust gets replaced by the certainty of good faith.

Last but not least, the issue of zkSNACKs’ censorship-friendly CoinJoin coordinator needs to be addressed. This is where everyone must understand the difference between the free open source software and the company behind it. Wasabi 2.0 is a non-custodial privacy wallet which doesn’t know who you are and empowers any individual or organization to run their own coordinator. If the default coordinator must abide by certain rules that don’t please certain privacy advocates, it doesn’t mean that these privacy advocates can’t tailor the software to suit their needs. As a matter of fact, having multiple coordinators for CoinJoins is largely beneficial for bitcoin privacy.

To zkSNACKs, the main priority is to be able to incentivize the 80+ developers and code contributors to keep on working towards building the best privacy wallet technology. Everyone is free to use Wasabi 2.0 however they please, there are certainly use cases that a registered company can’t support or endorse, and this is why you can switch the CoinJoin coordinator without needing to fork the code or make any other modifications. The bootstrapping of alternative Wasabi 2.0 CoinJoin coordination servers is instantaneous and easy.

As a side effect of the blacklisting of certain UTXOs that are associated with criminal activities, the fungibility of the mixes might get boosted. Previously, exchanges and other regulated businesses would flag incoming transactions whose immediate history is associated with CoinJoin rounds specifically because they needed to verify that the money doesn’t come from illegal activities. Now that the ZK Snacks coordinator will automatically decline UTXOs that exchanges don’t like, the exchanges themselves will have no excuse to reject any CoinJoins from this coordinator. This means that the CoinJoins will have the potential to go mainstream and help users transferring BTC from Coinbase to Kraken without informing the two entities about the ways in which some of the money might have been previously spent.

Wasabi 2.0 is a bridge for three reasons: it makes privacy easier, more affordable, and more acceptable. Anyone will be able to use the wallet correctly without making rookie consolidation mistakes that ruin the CoinJoin effort. Everyone will be able to use the open-source software with the CoinJoin coordinator that they like the most and poses the smallest amount of compromises. And thanks to a less popular move, exchanges will have no valid reasons to reject or even flag CoinJoin transactions.

Wasabi 2.0 bridges regulated institutions and cypherpunks. It bridges privacy advocates with the software that they’re going to want to use to coordinate their own mixes. And ultimately, it bridges privacy and fungibility. Thanks to Wasabi 2.0, bitcoin might just become as private and fungible as physical cash.